Greed and Capitalism

What kind of society isn't structured on greed? The problem of social organization is how to set up an arrangement under which greed will do the least harm; capitalism is that kind of a system.

- Milton Friedman

Sunday, December 29, 2013

Saturday, December 28, 2013

Friday, December 27, 2013

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Market Wisdom

"In the argument over the what and the when, I believe the what will invariably win over the when." Taking the Long View, Jean Riboud, CEO, Slumberger

Feeling the pure joy of work and success - jumping out of bed in the morning charged up to accomplish something in the day ahead - is necessary for an entrepreneur.

- T. Boone Pickens

I hate to fail, but when it's time to take a bath, I get in the tub...

- T. Boone Pickens

...................

Gerald Loeb:

The person who studies a problem from every angle and defines the risks, aims and possibilities correctly before he starts is more than halfway to his goal.

Diversification is necessary for beginners but the real great fortunes were made by concentration.

In the end, we are judged by our contribution.

.............................

The virtue of prosperity is temperance; the virtue of adversity is fortitude. -Francis

Bacon, 1625

.................................

Peter Drucker (October 23, 1987)

Wall Street traders are like Balkan peasants stealing each others sheep...

The last two years were just too disgusting a spectacle, and you know it won't last long...

When you reach the point where the traders make more money than the investors, you know its not going to last.

He stresses two points in particular: that any speculative bubble must burst, and that the inexperience of many youthful brokers has been an important factor in the recently unstable markets.

The average duration of a soap bubble is known - it's about 26 seconds then the surface tension becomes too great and it burstd. For speculative crazes, it's about 18 months.

The bubble had to burst partly because there is no foundation there, partly because there is no thinking there, and partly because their horizon has become the next 10 minutes. And the anybody whoe cries "Fire!" sets off a panic. You don't even have to cry fire. If somebody leaves the house, they - the traders - suspect there is a fire.

When you look at who dominates the scene, they are mostly people who weren't there five years ago - and who have absolutely no judgement... they keep endless hours, but that is not the same thing as doing any thinking or doing any work.

......................................

"When beggars and shoeshine boys, barbers and beauticians can tell you how to get rich, it is time to remind yourself that there is no moredangerous illusion than the belief that you can get something for nothing."

-Bernard Baruch, mid-1920's

Stock profits begin with the perception of a few and end with the conviction of many.

- A. Zeikel, Merrill Lynch Asset Management

Conservative investors are not risk takers, they are risk averters. They study a deal from all angles and are not afraid to walk away from a deal that is not shaping up right. They want to understand the risks and to reduce them where possible. They bide their time and try to massage the 'deck' to the point hwere the odds are 9 out 10 in their favor. Otherwise they look elsewhere to invest. Nobody in their right mind wants to be a risk taker...

Rules for a Bear Market: When in doubt, let the market shake out and sell on rallies. Forget any notions that the market is cheap0, because share prices when share prices fall out of the stratosphere, they may still be expensive from an intrinsic value point of view.

"If you have trouble imagining a 20% loss in the stock market, you shouldn't be in stocks." John (Jack) Bogle

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Friday, December 13, 2013

How Does Apple Really Feel About Bitcoin?

View on web:

Source: TechCrunch

@TechCrunch

........................

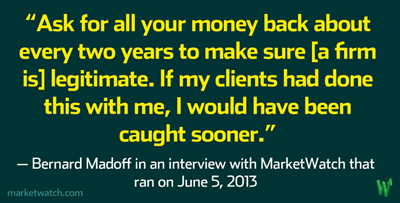

Criminal Action Is Expected for JPMorgan in Madoff Case

By JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERG and BEN PROTESS

Federal authorities and JPMorgan Chase are expected to settle

charges over ties to Bernard L. Madoff, who operated a billion-dollar

Ponzi scheme using an account at the bank.

For more top news, go to NYTimes.com »

.................................

By SABRINA TAVERNISE

The move was a major shift that could have far-reaching implications for industrial farming and human health.

|

Thursday, December 12, 2013

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

Exclusive Interview With Michael Gayed: Pension Partners

http://youtu.be/ZavzT6Msw4U

Exclusive Interview With Michael Gayed: Pension Partners

An exclusive interview with Michael Gayed, CFA, Chief Investment

Strategist, Pension Partners. Michael takes a look back at 2013 and a

look ahead at opportunities and challenges for 2014.

Sunday, December 8, 2013

Commit fraud and get away with it

How to commit fraud and get away with it:

A Guide for CEOs

Shorter Version

A strategy to maximize bonuses and avoid personal culpability:- Don’t commit the fraud yourself.

- Minimize information received about the actions of your employees.

- Control employees through automated, algorithmic systems based on plausible metrics like Value at Risk.

- Pay high bonuses to employees linked to “stretch” revenue/profit targets.

- Fire employees when targets are not met.

- …..Wait.

..................................

A Guide for CEOs

Longer Version

CEOs and senior managers of modern corporations possess the ability to engineer fraud on an organisational scale and capture the upside without running the risk of doing any jail time.In other words, they can reliably commit fraud and get away with it.

Imagine that you are the newly hired CEO of a large bank and by some improbable miracle your bank is squeaky clean and free of fraudulent practises. But you are unhappy about this.

Your competitors are making more profits than you are by embracing fraud and coming out ahead of you even after paying tens of billions of dollars in fines to the regulators. And you want a piece of the action.

But you’re a risk-averse person and don’t want to risk spending any time in jail for committing fraud. So how can you achieve this outcome?

Obviously you should not commit any fraudulent acts yourself. You want your junior managers to commit fraud in the pursuit of higher profits. One way to incentivise this behaviour is to adopt what are known as ‘high-powered incentives’.

Pay your employees high bonuses tied to revenue/profits and maintain hard-to-meet ‘stretch’ targets. Fire ruthlessly if these targets are not met.

And finally, ensure that you minimise the flow of information up to you about how exactly how your employees meet these targets.

There is one problem with this approach. As a CEO, this allows you to use the “I knew nothing!” defense and claim ignorance about all the “deplorable” fraud taking place lower down the organisational food chain.

But it may fall foul of another legal principle that has been tailored for such situations – the principle of ‘wilful blindness’ – “if there is information that you could have know, and should have known, but somehow managed not to know, the law treats you as though you did know it”.

In a recent essay, Judge Rakoff uses exactly this principle to criticise the failure of regulators in the United States in prosecuting senior bankers.

But wait – all hope is not lost yet.

There is one way by which you as a CEO can not only argue that adequate controls and supervision were in place and at the same time make it easier for your employees to commit fraud. Simply perform the monitoring and control function through an automated system and restrict your role to signing off on the risk metrics that are the output of this automated system.

It is hard to explain how this can be done in the abstract so let me take a hypothetical example from the mortgage origination and securitisation industry. As a CEO of a mortgage originator in 2005, you are under a lot of pressure from your shareholders to increase subprime originations. You realise that the task would be a lot easier if your salespeople originated fraudulent loans where ineligible borrowers are given loans they can’t afford.

You’ve followed all the steps laid out above but as discussed this is not enough. You may be accused of not having any controls in the organisation. Even if you try hard to ensure that no information regarding fraud filters through to you, you can never be certain.

At the first sign of something unusual, a mortgage approval officer may raise an exception to his supervisor. Given that every person in the management hierarchy wants to cover his own back, how can you ensure that nothing filters up to you whilst at the same time providing a plausible argument that you aren’t wilfully blind?

The answer is somewhat counterintuitive – you should codify and automate the mortgage approval process. Have your salespeople input potential borrower details into a system that approves or rejects the loan application based on an algorithm without any human intervention. The algorithm does not have to be naive. In fact it would ideally be a complex algorithm, maybe even ‘learned from data’.

Why so? Because the more complex the algorithm, the more opportunities it provides to the salespeople to ‘game’ and arbitrage the system in order to commit fraud. And the more complex the algorithm, the easier it is for you, the CEO, to argue that your control systems were adequate and that you cannot be accused of willful blindness or even the ‘failure to supervise’.

In complex domains, this argument is impossible to refute. No regulator/prosecutor is going to argue that you should have installed a more manual control system. And no regulator can argue that you, the CEO, should have micro-managed the mortgage approval process.

Let me take another example – the use of Value at Risk (VaR) as a risk measure for control purposes in banks. VaR is not ubiquitous because traders and CEOs are unaware of its flaws.

It is ubiquitous because it allows senior managers to project the facade of effective supervision without taking on the trouble or the legal risks of actually monitoring what their traders are up to.

It is sophisticated enough to protect against the charge of wilful blindness and it allows ample room for traders to load up on the tail risks that fund the senior managers’ bonuses during the good times. When the risk blows up, the senior manager can simply claim that he was deceived and fire the trader.

What makes this strategy so easy to implement today compared to even a decade ago is the ubiquitousness of fully algorithmic control systems. When the control function is performed by genuine human domain experts, then obvious gaming of the control mechanism is a lot harder to achieve.

Let me take another example to illustrate this. One of the positions that lost UBS billions of dollars during the 2008 financial crisis was called ‘AMPS’ where billions of dollars in super-senior tranche bonds were hedged with a tiny sliver of equity tranche bonds so that the portfolio showed a zero VaR and delta-neutral risk position.

Even the most novice of controllers could have identified the catastrophic tail risk embedded in hedging a position where one can lose billions, with another position where one could only gain millions.

There is nothing new in what I have laid out in this essay – for example, Kenneth Bamberger has made much the same point on the interaction between technology and regulatory compliance:

automated systems—systems that governed loan originations, measured institutional risk, prompted investment decisions, and calculated capital reserve levels—shielded irresponsible decisions, unreasonably risky speculation, and intentional manipulation, with a façade of regularity….

Invisibility by design, allows engineering of fraudulent outcomes without being held responsible for them – the “I knew nothing!” defense. of course, they are also self-deceived so this is really true.But although the automation that enables this risk-free fraud is a recent phenomenon, the principle behind this strategy is one that is familiar to managers throughout the modern era – “How do I get things done the way I want to without being held responsible for them?”.

Just as the algorithmic revolution is simply a continuation of the control revolution, the ‘accountability gap’ due to automation is simply an acceleration of trends that have been with us throughout the modern era.

Theodore Porter has shown how the rise of objectivity and bureaucracy were as much driven by the desire to avoid responsibility as they were driven by the desire for superior results.

Many features of the modern corporate world only make sense when we understand that one of their primary aims is the avoidance of responsibility and culpability. Why are external consulting firms so popular even when the CEO knows exactly what he wants to do? So that the CEO can avoid responsibility if the ‘strategic restructuring’ goes badly.

Why do so many firms delegate their critical control processes to a hotpotch of outsourced software contractors? So that they can blame any failures on external counter-parties who have explicitly been granted exemption from any liability1.

Due to my experience in banking, my examples and illustrations are necessarily drawn from the world of finance. But it should be clear that nothing in what I’ve said is limited to banking.

‘Strategic ignorance’ is equally effective in many other domains. My arguments are also not a justification for not prosecuting bankers for fraud. It is an argument that CEOs of modern corporations can reap the benefits of fraud and get away with it. And they can do so very easily. Fraud is embedded within the very fabric of the modern economy.

Note: Venkat makes a similar point in his series on the ‘Gervais Principle’ on how sociopathic managers avoid responsibility for their actions. Much of what I have written above may make more sense if read in conjunction with his essay.

macroresilience

resilience, not stability

- Helen Nissenbaum makes this and many other relevant points in her paper about ‘accountability in a computerised society’. ↩

................................

This is someone I follow on Twitter and he is a skeptic of

pretty much everything... he tweeted about how to commit fraud as the

CEO and face no consequences... the article is on an interesting Blog.

Twitter really suits the skimming of headlines kind of information gathering.

Source:

How to commit fraud and get away with it: A Guide for CEOs

macroresilience

resilience, not stability

About/Contact Me

The Author

Name: Ashwin Parameswaran

Occupation: Ex-banker (fixed income structuring for 7 years), currently working on a startup.

Location: London, UK

Education: IIM, Ahmedabad

Email: macroresilience (at) gmail (dot) com

Google Plus: https://plus.google.com/108131709155063176773/

Twitter: http://twitter.com/macroresilience

The Blog

Mostly about markets and macroeconomies as complex adaptive systems (emphasis on “adaptive”), sometimes about banking. A way to force myself to organise my thoughts and get feedback from others.

Bitcoin a Bubble Says Greenspan

Friday, December 6, 2013

Buisiness Tweets

http://bit.ly/IukKLT

..................................

RT @LGers: A financial to-do list for the end of the year.

Amazon's Drones

Almost 1/3 of US bank tellers rely on public assistance

@davjolly

Holy Smokes! Where those Wall Street profits come from: Almost 1/3 of US bank tellers rely on public assistance

Commodity Trading Advisors Fool Some People All Of The Time

Hedge funds are able to charge large fees based on the premise that

their unique skills allow them to generate risk-adjusted outperformance

(alpha) after expenses. Apparently investors believe the...

Seeking Alpha @SeekingAlpha 4m

Commodity Trading Advisors Fool Some People All Of The Time http://seekingalpha.com/article/1881841-commodity-trading-advisors-fool-some-people-all-of-the-time?source=feed_f …

Thursday, December 5, 2013

Buffett's Berkshire buys sizable new Exxon Mobil stake

By Jonathan Stempel and Luciana Lopez

Warren Buffet, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, leaves the first session of the annual Allen and Co. conference at the Sun Valley, Idaho Resort July 10, 2013.

Credit: Reuters/Rick Wilking

Buffett's Berkshire buys sizable new Exxon Mobil stake

(Reuters) - Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc on Thursday disclosed a new $3.45 billion stake in Exxon Mobil Corp, after buying 40.1 million shares in the world's largest publicly traded oil company.

Although the investment represents just 0.9 percent of Houston-based Exxon's shares, analysts said it reflects strong support by the second-richest American of one of the world's largest and most profitable companies.

Berkshire already has energy and utilities businesses, including MidAmerican Energy, which is spending $5.6 billion to buy Nevada utility NV Energy Inc.

"Buffett is a classic value investor, and Exxon has been an under-loved stock in a bull market," Molchanov said. "Exxon is an amazing cash generating machine, which should generate $16 billion of free cash flow this year."

Berkshire also reported higher stakes in Bank of New York Mellon Corp, dialysis clinic operator DaVita HealthCare Partners Inc, satellite TV provider DIRECTV, Suncor Energy Co, US Bancorp and Verisign Inc, which assigns Internet protocol addresses. Its stake in drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline Plc fell.

Berkshire also owns more than 80 businesses in such areas as insurance, railroads, utilities, chemicals and food. It paid $12.3 billion in June for half of ketchup maker H.J. Heinz Co.

On Thursday, Berkshire's Class A shares rose 0.7 percent to $173,320, and its Class B shares rose 0.8 percent to $115.69.

(Additional reporting by Anna Driver; Editing by Gary Hill,Ken Wills and Bob Burgdorfer)

Related Video

Source: http://www.reuters.com/article/video/idUSBRE9AD1BO20131115?videoId=274534783

Turning $1,000 Into $42 Million

Ken Fisher Contributor

29-year Forbes columnist, money manager and bestselling author.

full bio →

Forbes

Turning $1,000 Into $42 Million

This story appears in the December 16, 2013 issue of Forbes.

I have been writing for this magazine for 29-plus years, and with this issue I pass Lucien O. Hooper to become the third-longest-running “expert” columnist in FORBES’ 96-year history.

Lucien may have been the most popular ever for what Steve Forbes recalls as his “conversational way,” and even though he died 25 years ago, his investing lessons still hold today.

Lucien oozed his Maine farm boy origins. A Harvard dropout, Lucien began at the bottom of the Boston Commercial in 1919, eventually overseeing statistics while penning a commodity column. Soon he was writing stock market commentary for multiple brokerage firms now long forgotten (remember E.A. Pierce?) and became a leader on security and financial analysis.

Lucien’s arrival at FORBES came via Helen Slade. If Ben Graham is the father of security analysis, then Helen is surely its mother. Ben, in fact, was Helen’s prime disciple. Number two? Lucien.

When Helen started The Analysts Journal in 1945 (today’s Financial Analysts Journal and the bible to the scholarly set), she had Ben and Lucien debate each other in the very first issue. (So typical of him, Lucien always said he lost. No one lost. Everyone won.)

Helen hosted legendary “Tipsters Wednesday night soirees” once a month–40 to 50 financial folk, swilling, spilling and grilling each other’s market ideas.

Even my introverted father attended when in New York, and one July evening in 1949 so did a 29-year-old Malcolm Forbes, who had an amazing knack for picking people and recognized that Lucien knew his stuff, made the abstract comfortable and endured where “smarter men usually fail,” as Lucien put it.

On Aug. 15, 1949 Lucien’s first column came out swinging–correctly claiming the three-year bear market was over. Stocks skyrocketed until 1956. He pushed people to quality growth shares, which also proved right then. Sure, he made mistakes–he missed the 1974 downturn and proved too cautious in the ensuing bull market, prompting him to wind up his column on Jan. 1, 1979. But overall he was more right than wrong.

In FORBES he coined classic lines like “[Investors] make more money with the seat of their pants than the soles of their feet.”

He called out-of-favor stocks “ex-friends and ex-possibilities.”

He explained the difference between short-term and long-term plays as the kind you “take out for the evening” versus ones you “take home to mamma.” (He dealt in both but said most folks “make more money with mamma.”)

His overarching counsel was to pick among his picks–then let the winners run very, very long.

In honor of Lucien here are five of his picks that I like now–and I show how rich you would be if you had put $1,000 then into each (in a tax-free account) when he first recommended them, and reinvested all dividends:

He recommended ROYAL DUTCH SHELL (RDS.B, 71) on Dec. 15, 1974. That $1,000 then is worth more than $452,000 now. I just recommended it again on Nov. 18.

My first big hit in life, in 1975, was coatings, glass and chemical maker PPG INDUSTRIES (PPG, 183) . I think it’s a potential hit again. Lucien’s Oct. 1, 1976 entry would turn $1,000 into more than $172,000 today.

One of my father’s early big hits was Motorola in 1953, now MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS (MSI, 65) . Lucien was there first on Feb. 1, 1950–and $1,000 then exceeds $735,000 now.

PROCTER & GAMBLE (PG, 85) should beat the rest of this bull market. Lucien’s pick at year-end 1950 would be worth more than $1.1 million now.

The topper? KANSAS CITY SOUTHERN (KSU, 122) –our very best railroad. Lucien picked it in his first column and many times since. A $1,000 stake on Aug. 15, 1949, reinvested, is worth more than $42 million now–one of history’s best picks and one worth repeating.

Then or now, you read it in FORBES first.

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Gold in trouble?

Gold working on a losing streak Friday, 29 Nov 2013

CNBC's Bertha Coombs reports on the divergence between WTI and Brent crude, and the rise in gold.

The spot gold price took its worst monthly tumble in November for 35 years, continuing the precious metal's steady decline in 2013.

As of Friday afternoon GMT, spot gold showed a decrease of around 5.5 percent for November. A price fall of such magnitude hasn't been seen in November since 1978, according to data from the World Gold Council, when prices plunged 20 percent.

"Gold's topsy-turvy year rolls on," Adrian Ash, head of research at BullionVault, said in a research note on Friday. "Thanks to the surging stock market, now at 6-year highs worldwide, there have been worse years for gold prices. But not many. By our maths, in fact, only two."

Stringer | AFP | Getty Images

November is historically a good month for gold. Bullion has gained 1.4 percent on average during the month over the last 45 years, according to research by online gold exchange BullionVault.

(Read More: With gold scarce, Indian wedding buyers recycle jewellery)

Ash pointed towards waning demand in India as a key reason behind the move south. Net gold imports to China – another major market for gold -- remain strong, but imports to India have been hit by a government clampdown. Fears over India's current account deficit have led to officials trying to curb the high level of gold imports.

China vs India: Who has stronger gold demand?

Miguel Perez-Santalla, VP of Bullion Vault, says China's growing economy allows it to have a stronger position on gold.

India was until recently the biggest consumer of gold, but has been overtaken by China, according to the World Gold Council. Diwali festivities and the upcoming wedding season are seen as traditional drivers of gold demand in November for India.

Spot gold rested at $1,252 an ounce on Friday and was headed for its biggest monthly drop since June. It has lost over a quarter of its value year-to-date, putting it on track to post its first annual loss in 13 years.

Gold surged around 400 percent between 2002 and 2012, helped by low interest rates, extra liquidity from the U.S. Federal Reserve and concerns over the global economy, which drove investors towards perceived safe-haven assets like bullion.

But with the Fed looking to take its foot off the gas in terms of its $85 billion per month asset purchases soon, many analysts predict gold could continue its move lower.

Citi said this month that gold was about to enter "phase two" of its bear market and its downside target for the metal is now $1,111 per ounce. Goldman Sachs, meanwhile, predicts a "significant decline" in gold in 2014, with a fall of at least 15 percent.

By CNBC.com's Matt Clinch. Follow him on Twitter @mattclinch81

Link: http://www.cnbc.com/id/101235384

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Twitter leaves more than $1 billion on the table

Twitter made a ton of money from its IPO, but its bankers got the better deal.

FORTUNE -- Twitter began trading this morning at $45.10 per share, after pricing its IPO last night at $26 per share. Or, put another way, Twitter (TWTR) left more than $1.3 billion on the table. Or, put even another way, more than twice what the company will generate in revenue this year.

As I type these words, Twitter stock has now topped $50 (bumping my $1.3 figure up to nearly $1.7 billion -- amazing, given that the actual IPO only raised $1.82 billion).

Twitter itself obviously wanted a bit of price pop for PR and employee morale purposes, but here's something else employees could be thinking about today: Had Twitter priced at $45.10 per share and used the extra proceeds to give out holiday bonuses, it would have worked out to more than $580,000 per employee.

--

Year-to-Date

Sign up for Dan's daily email newsletter on deals and deal-makers: GetTermSheet.com

By Dan Primack November 7, 2013

Read more @ Source: http://finance.fortune.cnn.com/2013/11/07/twitter-leaves-more-than-1-billion-on-the-table/

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

JPMorgan agrees to $13 billion settlement over mortgages

The deal includes:

i) $9 billion in payments to authorities and

ii) $4 billion in relief to consumers – mainly homeowners

November 19, 2013

JPMorgan Chase & Co. has agreed to a record $13 billion settlement over mislabeled mortgage securities that federal and state authorities said stoked the financial crisis, the Department of Justice announced Tuesday.

The deal includes $9 billion in payments to authorities and $4 billion in relief to consumers – mainly homeowners – harmed by the conduct of JPMorgan and the two failed banks it took over during the crisis, Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual.

The bank "acknowledged it made serious misrepresentations to the public – including the investing public" over the quality of residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) it sold ahead of the financial crisis, the Justice Department said in a statement.

As the housing market collapsed between 2006 and 2008, millions of homeowners defaulted on high-risk mortgages. That led to billions of dollars in losses for investors who bought securities created from bundles of mortgages. Those securities were sold by JP Morgan and other big Wall Street banks.

"Without a doubt, the conduct uncovered in this investigation helped sow the seeds of the mortgage meltdown," Attorney General Eric Holder said.

"JPMorgan was not the only financial institution during this period to knowingly bundle toxic loans and sell them to unsuspecting investors, but that is no excuse for the firm's behavior."

Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and other big banks have similarly been accused by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of deceiving investors in sales of mortgage securities in the runup to the crisis. Together they have paid hundreds of millions in penalties to settle civil charges brought by the SEC.

Record-setting penalty

The agreement eclipses the previous record government fine of a private corporation and resolves a major part of a series of complaints against the largest U.S. bank over mortgage securities that caused huge investor losses.

The agreement announced Tuesday clears most of the civil allegations over mortgage securities against the banks. However, the Justice Department said the deal still does not absolve the bank or its employees from possible criminal charges.

Consumer relief

The complex deal includes claims and penalties to be paid to the Justice Department, the National Credit Union Administration, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and the states of California, Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts and New York.

The $4 billion for consumer relief requires JPMorgan to forgive some of the principal on many customers' loans and modify others to improve conditions for borrowers.

READ MORE:

Link: http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2013/11/19/jpmorgan-agrees-to13bdealformortgagemisdeeds.html

Friday, November 15, 2013

JPMorgan reaches $4.5B investor settlement

The Associated Press, November 15, 2013

Bank is close to deal with 21 institutional investors with losses on mortgage-backed securities.

JPMorgan reaches $4.5B investor settlement

NEW YORK (AP) — JPMorgan says reaches $4.5 billion settlement with investors on mortgage-backed securities.

During the regular trading session, shares of JPMorgan ended up 47 cents, 0.9%, to $54.87. In after-hours trading Friday, shares gained 14 cents, 0.3%, to $55.01.

Story: Backlash causes JPMorgan to cancel Twitter chat

Story: JPMorgan to pay $5.1 billion to feds in mortgage deal

Story: Citigroup, JPMorgan, RBS confirm foreign exchange probes

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Link: http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2013/11/15/jpmorgan-reaches-multibillion-dollar-settlement/3593475/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter&dlvrit=110940

Mark Spangler is an Investment Adviser Gone Astray

Wealth Matters: The Cautionary Tale of an Investment Adviser Gone Astray

.....................................................

SEC Charges Seattle-Based Fund Manager for Secretly Diverting Client Funds to His Own Start-Up Companies

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

2012-95

Washington, D.C., May 17, 2012 —

The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged a Seattle-based investment adviser and his firm with defrauding clients by secretly investing their money in two risky start-up companies he co-founded.

The SEC alleges that Mark Spangler, a former chairman of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors, funneled approximately $47.7 million of client money into these private ventures despite representing that he would invest primarily in publicly-traded securities.

2012-95

Washington, D.C., May 17, 2012 —

The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged a Seattle-based investment adviser and his firm with defrauding clients by secretly investing their money in two risky start-up companies he co-founded.

The SEC alleges that Mark Spangler, a former chairman of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors, funneled approximately $47.7 million of client money into these private ventures despite representing that he would invest primarily in publicly-traded securities.

Spangler served as chairman and CEO of one of the companies, which is now bankrupt. Such risky investments were inconsistent with the investment strategies that Spangler promised his clients and contrary to their investment objectives.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington today announced parallel criminal charges against Spangler.

“Spangler assured his clients he was investing them in publicly-traded equities and bonds, not risky start-ups in which he had a personal interest,” said Marc Fagel, Director of the SEC’s San Francisco Regional Office.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington today announced parallel criminal charges against Spangler.

“Spangler assured his clients he was investing them in publicly-traded equities and bonds, not risky start-ups in which he had a personal interest,” said Marc Fagel, Director of the SEC’s San Francisco Regional Office.

“For an investment adviser to put his self-interest above the best interests of his clients is a disturbing abuse of trust.”

According to the SEC’s complaint filed in federal court in Seattle, Spangler raised more than $56 million from his clients since 1998 for several private investment funds he managed.

According to the SEC’s complaint filed in federal court in Seattle, Spangler raised more than $56 million from his clients since 1998 for several private investment funds he managed.

Beginning around 2003, without notifying investors in the funds, Spangler and his advisory firm The Spangler Group (TSG) began diverting the majority of client money into two private technology companies he created.

One of the companies received nearly $42 million from the funds before shutting down operations. It had long been a cash-poor company with a history of net losses, generating less than $100,000 in revenue during its

Yet Spangler continued to treat the funds as the company’s piggy bank.

The SEC alleges that Spangler also did not tell investors that TSG collected fees for “financial and operational support” from these companies, which were essentially paying these fees with the client money they had received from the funds. Therefore, Spangler and his firm secretly reaped $830,000 from the companies in addition to any management fees that TSG received from clients.

According to the SEC’s complaint, Spangler concealed his diversion of client funds for years. He disclosed it only after he placed TSG and the funds he managed into state court receivership in 2011.

The SEC’s complaint charges Spangler and TSG with violating, among other things, the antifraud provisions of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The complaint seeks injunctive relief, disgorgement with prejudgment interest, and financial penalties.

The SEC’s investigation was conducted by Karen Kreuzkamp and Robert S. Leach of the San Francisco Regional Office with assistance from Michael Tomars, Peter Bloom, and Christine Pelham of the investment adviser/investment company examination program. Robert L. Tashjian will lead the SEC’s litigation.

The SEC thanks the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Internal Revenue Service for their assistance in this matter.

The SEC alleges that Spangler also did not tell investors that TSG collected fees for “financial and operational support” from these companies, which were essentially paying these fees with the client money they had received from the funds. Therefore, Spangler and his firm secretly reaped $830,000 from the companies in addition to any management fees that TSG received from clients.

According to the SEC’s complaint, Spangler concealed his diversion of client funds for years. He disclosed it only after he placed TSG and the funds he managed into state court receivership in 2011.

The SEC’s complaint charges Spangler and TSG with violating, among other things, the antifraud provisions of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The complaint seeks injunctive relief, disgorgement with prejudgment interest, and financial penalties.

The SEC’s investigation was conducted by Karen Kreuzkamp and Robert S. Leach of the San Francisco Regional Office with assistance from Michael Tomars, Peter Bloom, and Christine Pelham of the investment adviser/investment company examination program. Robert L. Tashjian will lead the SEC’s litigation.

The SEC thanks the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Internal Revenue Service for their assistance in this matter.

###

November 15, 2013

The Cautionary Tale of an Investment Adviser Gone Astray

By PAUL SULLIVAN

IN the world of Ponzi schemes, Mark Spangler was a small-time crook. But his early career, as a respected investment adviser in Seattle and onetime head of a national adviser organization that pushes its members to act in their clients’ best interest, gives his recent conviction on 32 criminal counts a twist.

At its height, the Spangler Group — which consisted of him and later his wife — supposedly managed $106 million. It collapsed in 2011 for the reason that all Ponzi schemes collapse — clients wanted their money back and he didn’t have it. But it had been coming undone for years, ever since Mr. Spangler, 58, started to fashion himself a venture capitalist, a role he was ill suited to.

He is now awaiting what could be a life sentence on charges of fraud, money-laundering and investment adviser fraud.

Mr. Spangler was convicted a month before a dreary holiday I proposed last year: Madoff Day — the anniversary of the collapse of Bernard L. Madoff’s Ponzi scheme on Dec. 10, 2008. As I suggested then, the day should be remembered to remind people why it is important to be as vigilant about assessing who manages their money as it is in evaluating a doctor.

Mr. Spangler’s Ponzi scheme started like any other. He ingratiated himself with a couple of wealthy groups — employees at Microsoft and Immunex, a biotechnology company now owned by Amgen — who referred their friends to him. He pitched the wealthier clients on private deals that would pay them a big return and him a high commission if they succeeded.

After a string of failures, he thought he had found two companies — TeraHop Networks, which made tracking devices, and Tamarac, a provider of software to financial advisers — that would make it big. For that to happen, they needed money, and he began diverting funds from the other accounts he managed to feed them. TeraHop struggled; Tamarac showed promise. But in 2010 clients began making withdrawals and he didn’t have the money to give them.

Mr. Spangler, who came from a well-known family in Seattle, began his career legitimately. He attended a prestigious Catholic prep school and the University of Washington. As his practice grew, he became the national chairman of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisers (Napfa), a group of fee-only advisers who commit to work in the best interests of their clients.

But by the early 2000s, he had become an advocate of private placements, risky, illiquid investments in little-known companies that promised a large return if they succeeded. Most of the ones Mr. Spangler picked failed.

“I remember him talking at a conference saying why he went away from publicly traded companies and into private partnerships because the returns were better,” said Nick Stuller, president and chief executive of Advice IQ, a company that evaluates advisers. “When I heard that, I said that is something really different, that’s very unusual.”

As Mr. Spangler’s failures mounted, he began dipping into the privately managed mutual funds — with names like Growth and Income — that he had for his more risk-averse clients. Those funds had been managed by outside advisers until 2003, when he decided to manage them himself. He told clients that this would save them on fees, but it really removed third-party oversight of his dealings. By the end, he had diverted the bulk of his clients’ money — some $43 million — to TeraHop, where he had become the chief executive, and Tamarac.

“He got bit by the venture capital bug,” said Mike Lang, an assistant United States attorney who was one of the prosecutors. “We’re in Seattle. Everyone is making money. He wanted a piece of that.”

Andrew Stoltmann, a Chicago securities lawyer, said what Mr. Spangler did happens more than people realize. “I can’t tell you how many brokers or investment advisers want to be hedge fund managers, mutual fund managers or investment bankers,” he said. “You see these guys doing this kind of stuff all the time — raising money for private companies or running their own mutual funds. Nine times out of 10 it ends disastrously with massive losses.”

Of course, there is a big a difference between getting clients’ consent to put money into private investments that might fail and doing it without their knowing.

When I first wrote about Mr. Spangler in 2011, shortly after federal agents seized his passport to keep him from fleeing to Ecuador with his wife, people who knew him were shocked.

Susan John, who was then the national chairwoman of Napfa, said she was struggling to reconcile the man she had known for 20 years with the one charged with fraud. This week, in an email, she said: “The whole affair saddens me greatly. Consumers need to use diligence when selecting an adviser and continue to monitor their investments periodically so that they notice any change in philosophy or implementation.”

Yet she conceded that Mr. Spangler had once had such a sterling reputation that it lulled clients into a false sense of security. “My personal opinion is that the entire regulatory framework needs to be re-evaluated so that consumers are better protected from those whose self-interest gets in the way of their better judgment,” she said.

Richard Boyd, who, along with his wife, ultimately lost $750,000, said he met Mr. Spangler for coffee several times after the firm was shut down. “He said, ‘Don’t worry. Everything will work out,’ ” said Mr. Boyd, who has a doctorate in molecular biology and worked at Immunex. “He was talking about being our adviser again once this all blew over.”

In his fraud, Mr. Spangler was a combination of the best — or worst, perhaps — of Mr. Madoff and R. Allen Stanford, who sold fraudulent certificates of deposit and was later convicted of a $7 billion fraud. Mr. Madoff ingratiated himself with the Jewish communities in New York and Palm Beach, while Mr. Spangler did the same with wealthy but financially naïve executives at Microsoft and Immunex.

Like Mr. Stanford, Mr. Spangler relied on people failing to read or understand what was on their quarterly statements. Reports from the Stanford Financial Group were filled with small quantities of legitimate securities and had a line or two at the end showing the bulk of the money was in certificates of deposit later determined to be fraudulent.

In Mr. Spangler’s statements, he provided only a breakdown of how money was allocated to his various funds.

“There was no indication on the statements,” Mr. Boyd said. “They painted a very rosy picture. They showed our basis and current value for every investment we had. Our money had grown by 40 percent.”

Mr. Boyd said there were never names of individual securities or mutual funds on the statements. Essex Porter, a television reporter at KIRO TV in Seattle, and his wife, who worked at Microsoft in the early 1990s, never suspected anything was awry. Even looking back, he said the only red flag was that the financial statements started to come less regularly toward the end.

It is often easy to spot the warning signs of a fraud in retrospect, but in this case they were subtle and showed the need for extra vigilance. Mr. Boyd said he once asked Mr. Spangler what stocks and funds he was invested in, but could not get a clear answer.

Ms. John said a third-party custodian could verify the holdings. But in Mr. Spangler’s case, he ceased to have one after 2003. By making himself a general partner in the private funds and investment vehicles, he could write himself a check to cover any expenses — or buy his $890,000 yacht.

“Only a small number of advisers put their money into nontransparent investments,” Mr. Stuller said. “A lot of questions have to be asked. You need to know who is the accounting firm? Who is the auditor? There is a great opportunity for fraud.”

But to be fair, spotting these warnings will be hard for clients with a trusting, even friendly relationship with their adviser.

Two years after his fraud was found out, his clients have fared better than most in similar schemes. They have been paid back about $29 million, which is a little less than half of the money they put in to the Spangler Group, according to Kent Johnson, the court-appointed receiver.

As for Mr. Spangler, his lawyer, Jon Zulauf, would say only: “This was a troubling verdict. Mr. Spangler believed that his investments were in the long-term best interests of his clients.”

Even if they had been, they were done without his clients’ knowledge. And it showed that even someone who claimed to be a fiduciary needed to be checked up on.

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/16/your-money/financial-planners/the-cautionary-tale-of-an-investment-adviser gone-astray.html?partner=socialflow&smid=tw-nytimesbusiness&_r=0

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)