Visual CapitalistVerified account @VisualCap

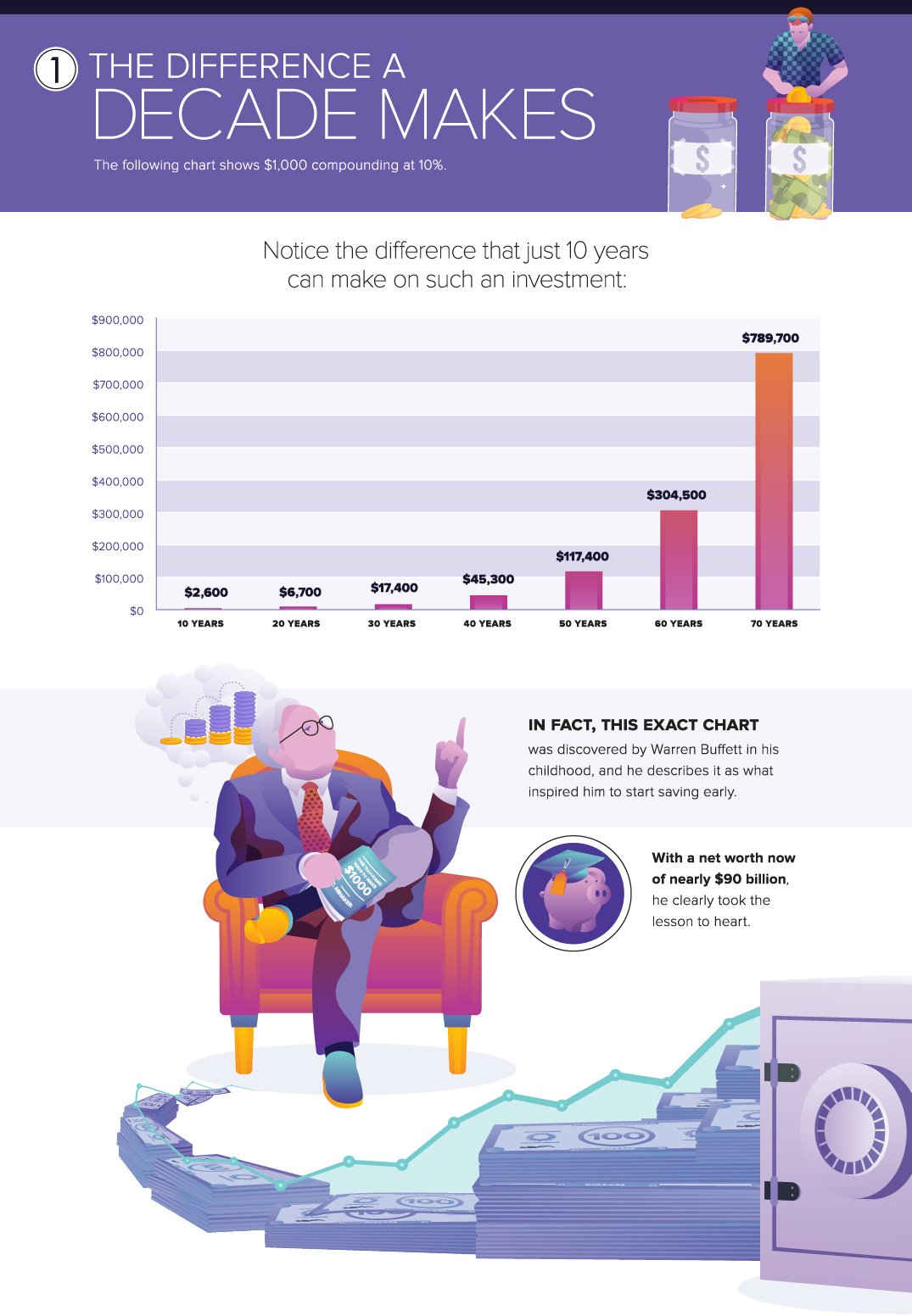

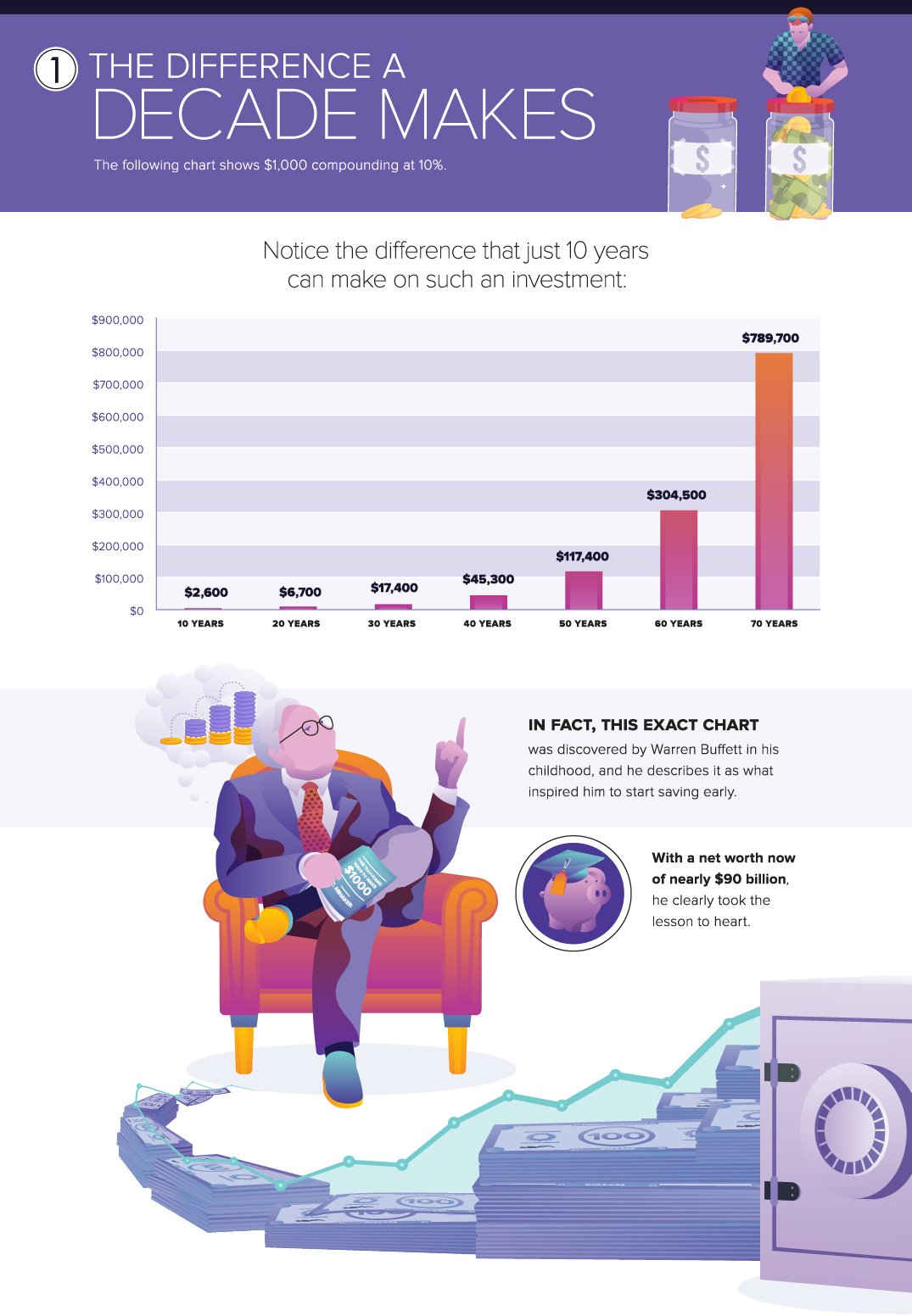

Infographic: Visualizing the Extraordinary Power of Compound Interest

(See all 3 examples: http://wealth.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-power-compound-interest/ …)

Since then the U.S. economy has changed: Consumer, finance, health care, and technology companies are more prominent today and the relative importance of industrial companies is less. Walgreens is a national retail drugstore chain offering prescription and nonprescription drugs, related health services, and general goods. With its addition, the DJIA will be more representative of the consumer and health-care sectors of the U.S. economy. Today’s change to the DJIA will make the index a better measure of the economy and the stock market.If you’re thinking, “That sounds kind of arbitrary,” you’re not wrong. How does adding up the share prices of 30 handpicked stocks and then dividing by a mutable “divisor” to normalize the index into a single number measure “the economy and the stock market”?