Global M&A at 7-year high, deal making frenzy seen absent geopolitical or economic shocks http://reut.rs/1z1UkqC

Greed and Capitalism

What kind of society isn't structured on greed? The problem of social organization is how to set up an arrangement under which greed will do the least harm; capitalism is that kind of a system.

- Milton Friedman

Monday, June 30, 2014

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Gold Royalty

Osisko Gold Royalties: This New Royalty/Exploration Company Is A Compelling Speculation Stock

Disclosure: The author is long RGLD, RPMGF. (More...)

Summary

- Osisko Gold Royalties is a new company formed out of the Agnico Eagle/Yamana Gold acquisition of Osisko Mining.

- It is a royalty company that is unique in that it isn't necessarily overvalued on a DCF basis, and it can use its royalty cash-flow to explore its Guerrero Project.

- The company is inexpensive relative to its peers, and it has the added optionality of an enormous exploration project as well as a royalty on a presently uneconomic gold project.

- Investors looking for a royalty company that hasn't yet been embraced by the market (e.g. Franco Nevada and Royal Gold) should consider taking a position.

An Overview Of Osisko Gold Royalties

Osisko Gold Royalties (OTC:OKSKF) is a new company formed out of Agnico Eagle's (AEM) and Yamana Gold's (AUY) acquisition of Osisko Mining. Osisko Mining shareholders received shares in each of these two companies plus a new company which trades now as Osisko Gold Royalties.

The company was formed because long term shareholders in Osisko Mining didn't want to give up their stakes in what was then that company's flagship mine--Canadian Malartic. The Canadian Malartic Project is one of the largest gold mines in Canada with 10 million ounces of gold reserves and another 12 million ounces of gold resources. The current mine plan calls for 14 years of 600,000+ ounces of production, but given the reserve size, the potential for resources to be converted into demonstrably economical reserves, and potential for exploration, the mine-life could be substantially longer than this.

The solution was to create Osisko Gold Royalties, whose primary asset is a 5% NSR royalty on the Canadian Malartic Project. This means that Osisko Gold Royalties will receive 5% of the gross revenues minus refining costs (which are essentially negligible) for the life of the mine. In addition the new company has the following assets:

- C$155 million in cash (about $145 million)

- A 2% NSR royalty on Osisko's Hammond Reef, and Kirkland Lake.

- The assets associated with (formerly) Osisko's Guerrero Mining Camp.

Friday, June 27, 2014

New York AG Schneiderman

BY TIM MCLAUGHLIN AND KAREN FREIFELD

NEW YORK Fri Jun 27, 2014 8:05pm EDT

New York AG Schneiderman finally flexes muscles against Wall Street

(Reuters) - New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, long seen as a secondary force in policing Wall Street banks, is taking the lead in what may be the most ambitious case of his career: accusing Barclays Plc (BARC.L) of favoring its high-frequency trading clients.

By making a case against the bank, Schneiderman has seized a lead role in a contentious dispute about whether high-frequency traders have turned the stock market into a rigged game that hurts regular investors.

The case against Barclays could lead to investigations into other Wall Street banks and define Schneiderman's career as an attorney general, lawyers say.

"It is the most important attack on practices in the market that any AG has engaged in in a while," said John Moscow, a former Manhattan prosecutor who now handles white-collar defense cases.

Barclays spokesman Mark Lane declined to comment on Friday.

A former state senator and corporate lawyer, Schneiderman is following a well worn path for New York attorney generals - taking on Wall Street and potentially winning political capital - and could end up, like Eliot Spitzer and Andrew Cuomo before him, as the state's governor. He declined to comment for this story.

Schneiderman, 59, graduated from Amherst College and earned a Harvard Law degree in 1982. He spent 15 years in corporate law, including as a partner at Kirkpatrick & Lockhart, where he handled white-collar defense cases. He served six terms as a state senator before running for attorney general, taking that office in 20ll.

Early in his tenure, Schneiderman was knocked for seeming more like the state legislator he used to be than a prosecutor. He has been less adept at grabbing headlines than Spitzer or Cuomo, and while he may have held banks accountable, he was less likely to push out ahead with cases.

In 2011, in his first year as attorney general, Schneiderman accused BNY Mellon Corp (BK.N), the world's largest custody bank, of overcharging pension funds on foreign currency trades, alleging the bank made $2 billion. But the civil action was hardly novel, as similar cases had already been filed in other parts of the country.

He is co-chair of a state-federal task force that in 2013 settled with JPMorgan Chase & Co (JPM.N) for $13 billion, with more than $600 million going to New York. The bank admitted to having routinely overstated the quality of mortgages it sold to bond investors before the housing crisis. He also is a key negotiator with Bank of America Corp (BAC.N) over similar claims. But banks have been settling with prosecutors and investors over these matters for years.

In contrast, Spitzer busted Wall Street with a $1.4 billion settlement with big banks and brokerages for urging customers to buy stocks that their analysts privately said were junk. Cuomo led a nationwide investigation into the auction-rate securities market, uncovering how the investments were marketed as safe when in reality they faced increasing liquidity risk. His investigation resulted in more than $60 billion in investor buybacks.

People close to Schneiderman characterize him as patient and low-key.... Schneiderman practices yoga.

But lawyers say that banks should not be fooled by Schneiderman's demeanor. He carries a big stick, namely the Martin Act, a New York state securities law that is powerful for prosecutors because it often does not require proof of intent to deceive. Some lawyers have criticized the law as too broad, with some saying it has been superseded by federal law.

"Another bank will pay enormous fines under a law that, in my mind, no longer exists,” said defense lawyer Robert McTamaney, a critic of the law, referring to the Barclays case.

(Reporting By Tim McLaughlin and Karen Freifeld; Editing by Dan Wilchins and Frances Kerry)

Link: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/06/28/us-banks-schneiderman-barclays-bk-idUSKBN0F22MU20140628

The Canadian Banking Fallacy

The Canadian Banking Fallacy

Posted on March 25, 2010 by Simon Johnson

By Peter Boone and Simon Johnson

As a serious financial reform debate heats up in the Senate, defenders of the new banking status quo in the United States today – more highly concentrated than before 2008, with six megabanks implicitly deemed “too big to fail” – often lead with the argument, “Canada has only five big banks and there was no crisis.” The implication is clear: We should embrace concentrated megabanks and even go further down the route; if the Canadians can do it safely, so can we.

It is true that during 2008 four of all Canada’s major banks managed to earn a profit, all five were profitable in 2009, and none required an explicit taxpayer bailout. In fact, there were no bank collapses in Canada even during the Great Depression, and in recent years there have only been two small bank failures in the entire country.

Advocates for a Canadian-type banking system argue this success is the outcome of industry structure and strong regulation. The CEOs of Canada’s five banks work literally within a few hundred meters of each other in downtown Toronto. This makes it easy to monitor banks. They also have smart-sounding requirements imposed by the government: if you take out a loan over 80% of a home’s value, then you must take out mortgage insurance. The banks were required to keep at least 7% tier one capital, and they had a leverage restriction so that total assets relative to equity (and capital) was limited.

But is it really true that such constraints necessarily make banks safer, even in Canada?

Despite supposedly tougher regulation and similar leverage limits on paper, Canadian banks were actually significantly more leveraged – and therefore more risky – than well-run American commercial banks. For example JP Morgan was 13 times leveraged at the end of 2008, and Wells Fargo was 11 times leveraged. Canada’s five largest banks averaged 19 times leveraged, with the largest bank, Royal Bank of Canada, 23 times leveraged. It is a similar story for tier one capital (with a higher number being safer): JP Morgan had 10.9% percent at end 2008 while Royal Bank of Canada had just 9% percent. JP Morgan and other US banks also typically had more tangible common equity – another measure of the buffer against losses – than did Canadian Banks.

If Canadian banks were more leveraged and less capitalized, did something else make their assets safer? The answer is yes – guarantees provided by the government of Canada. Today over half of Canadian mortgages are effectively guaranteed by the government, with banks paying a low price to insure the mortgages. Virtually all mortgages where the loan to value ratio is greater than 80% are guaranteed indirectly or directly by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (i.e., the government takes the risk of the riskiest assets – nice deal if you can get it). The system works well for banks; they originate mortgages, then pass on the risk to government agencies. The US, of course, had Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but lending standards slipped and those agencies could not resist a plunge into assets more risky than prime mortgages. Let’s see how long Canada resists that temptation.

The other systemic strength of the Canadian system is camaraderie between the regulators, the Bank of Canada, and the individual banks. This oligopoly means banks can make profits in rough times – they can charge higher prices to customers and can raise funds more cheaply, in part due to the knowledge that no politician would dare bankrupt them. During the height of the crisis in February 2009, the CEO of Toronto Dominion Bank brazenly pitched investors: “Maybe not explicitly, but what are the chances that TD Bank is not going to be bailed out if it did something stupid?” In other words: don’t bother looking at how dumb or smart we are, the Canadian government is there to make sure creditors never lose a cent. With such ready access to taxpayer bailouts, Canadian banks need little capital, they naturally make large profit margins, and they can raise money even if they act badly.

Proposing a Canadian-type model to create stability in the U.S. is, to be blunt, nonsense. We would need to merge our banks into even fewer banking giants, and then re-inflate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to guarantee some of the riskiest parts of the bank’s portfolios. With our handful of new “hyper megabanks”, we’d have to count on our political system to prevent our banks from going wild; Canada may be able to do this (in our view, the jury is still out), but what are the odds this would work in Washington? This would require an enormous leap of faith in our regulatory system immediately after it managed to fail repeatedly and spectacularly over thirty years (see 13 Bankers, out next week, for the awful details). Who can be confident our powerful corporate lobbies, hired politicians, and captured regulators can become so Canadian so soon?

The stakes would be even greater with these mega banks. When such large banks collapse they can take down the finances of entire nations. We don’t need to look far to see how “Canadian-type systems” eventually fail. Britain’s largest bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland, grew to control assets equal to around 1.7 times British GDP before it spectacularly fell apart and required near complete nationalization in 2008-09. In Ireland the three largest banks’ assets combined reached roughly 2.5 times GDP before they collapsed. Today all the major Canadian banks have ambitious international expansion plans – let’s see how long their historically safe system survives the new hubris of its managers.

There’s no doubt that during the coming months many people will advocate some form of a Canadian banking system in America. Our largest banks and their lobbyists on Capitol Hill will love the idea. For some desperate politicians it may become a miracle drug: a new “safer” system that will lend to homeowners and provide financing to Washington, while permitting politicians and regulators to avoid tough steps. Let’s hope this elixir doesn’t gain traction; smaller banks with a lot more capital – and able to fail when they act stupid – are what U.S. citizens and taxpayers really need.

An edited version of this post appeared on the NYT’s Economix this morning; it is used here with permission. If you wish to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times

Site:

The Baseline Scenario

What happened to the global economy and what we can do about it

Link: http://baselinescenario.com/2010/03/25/the-canadian-banking-fallacy/

Posted on March 25, 2010 by Simon Johnson

By Peter Boone and Simon Johnson

As a serious financial reform debate heats up in the Senate, defenders of the new banking status quo in the United States today – more highly concentrated than before 2008, with six megabanks implicitly deemed “too big to fail” – often lead with the argument, “Canada has only five big banks and there was no crisis.” The implication is clear: We should embrace concentrated megabanks and even go further down the route; if the Canadians can do it safely, so can we.

It is true that during 2008 four of all Canada’s major banks managed to earn a profit, all five were profitable in 2009, and none required an explicit taxpayer bailout. In fact, there were no bank collapses in Canada even during the Great Depression, and in recent years there have only been two small bank failures in the entire country.

Advocates for a Canadian-type banking system argue this success is the outcome of industry structure and strong regulation. The CEOs of Canada’s five banks work literally within a few hundred meters of each other in downtown Toronto. This makes it easy to monitor banks. They also have smart-sounding requirements imposed by the government: if you take out a loan over 80% of a home’s value, then you must take out mortgage insurance. The banks were required to keep at least 7% tier one capital, and they had a leverage restriction so that total assets relative to equity (and capital) was limited.

But is it really true that such constraints necessarily make banks safer, even in Canada?

Despite supposedly tougher regulation and similar leverage limits on paper, Canadian banks were actually significantly more leveraged – and therefore more risky – than well-run American commercial banks. For example JP Morgan was 13 times leveraged at the end of 2008, and Wells Fargo was 11 times leveraged. Canada’s five largest banks averaged 19 times leveraged, with the largest bank, Royal Bank of Canada, 23 times leveraged. It is a similar story for tier one capital (with a higher number being safer): JP Morgan had 10.9% percent at end 2008 while Royal Bank of Canada had just 9% percent. JP Morgan and other US banks also typically had more tangible common equity – another measure of the buffer against losses – than did Canadian Banks.

If Canadian banks were more leveraged and less capitalized, did something else make their assets safer? The answer is yes – guarantees provided by the government of Canada. Today over half of Canadian mortgages are effectively guaranteed by the government, with banks paying a low price to insure the mortgages. Virtually all mortgages where the loan to value ratio is greater than 80% are guaranteed indirectly or directly by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (i.e., the government takes the risk of the riskiest assets – nice deal if you can get it). The system works well for banks; they originate mortgages, then pass on the risk to government agencies. The US, of course, had Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but lending standards slipped and those agencies could not resist a plunge into assets more risky than prime mortgages. Let’s see how long Canada resists that temptation.

The other systemic strength of the Canadian system is camaraderie between the regulators, the Bank of Canada, and the individual banks. This oligopoly means banks can make profits in rough times – they can charge higher prices to customers and can raise funds more cheaply, in part due to the knowledge that no politician would dare bankrupt them. During the height of the crisis in February 2009, the CEO of Toronto Dominion Bank brazenly pitched investors: “Maybe not explicitly, but what are the chances that TD Bank is not going to be bailed out if it did something stupid?” In other words: don’t bother looking at how dumb or smart we are, the Canadian government is there to make sure creditors never lose a cent. With such ready access to taxpayer bailouts, Canadian banks need little capital, they naturally make large profit margins, and they can raise money even if they act badly.

Proposing a Canadian-type model to create stability in the U.S. is, to be blunt, nonsense. We would need to merge our banks into even fewer banking giants, and then re-inflate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to guarantee some of the riskiest parts of the bank’s portfolios. With our handful of new “hyper megabanks”, we’d have to count on our political system to prevent our banks from going wild; Canada may be able to do this (in our view, the jury is still out), but what are the odds this would work in Washington? This would require an enormous leap of faith in our regulatory system immediately after it managed to fail repeatedly and spectacularly over thirty years (see 13 Bankers, out next week, for the awful details). Who can be confident our powerful corporate lobbies, hired politicians, and captured regulators can become so Canadian so soon?

The stakes would be even greater with these mega banks. When such large banks collapse they can take down the finances of entire nations. We don’t need to look far to see how “Canadian-type systems” eventually fail. Britain’s largest bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland, grew to control assets equal to around 1.7 times British GDP before it spectacularly fell apart and required near complete nationalization in 2008-09. In Ireland the three largest banks’ assets combined reached roughly 2.5 times GDP before they collapsed. Today all the major Canadian banks have ambitious international expansion plans – let’s see how long their historically safe system survives the new hubris of its managers.

There’s no doubt that during the coming months many people will advocate some form of a Canadian banking system in America. Our largest banks and their lobbyists on Capitol Hill will love the idea. For some desperate politicians it may become a miracle drug: a new “safer” system that will lend to homeowners and provide financing to Washington, while permitting politicians and regulators to avoid tough steps. Let’s hope this elixir doesn’t gain traction; smaller banks with a lot more capital – and able to fail when they act stupid – are what U.S. citizens and taxpayers really need.

An edited version of this post appeared on the NYT’s Economix this morning; it is used here with permission. If you wish to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times

Simon Johnson @baselinescene

Simon Johnson. Co-author of White House Burning (WhiteHouseBurning.com) and 13 Bankers (13bankers.com).

Site:

The Baseline Scenario

What happened to the global economy and what we can do about it

Link: http://baselinescenario.com/2010/03/25/the-canadian-banking-fallacy/

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Arithmetic, Population, and Energy

Dr. Albert A. Bartlett from the University of Colorado in Boulder gives a simple, and fully comprehensive lecture on the most important issues facing humans today and demonstrates that "the greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function."

Category

License

Standard YouTube License

Link: http://youtu.be/vII-GxsrR2c

Link:http://youtu.be/DZCm2QQZVYk

Thursday, June 12, 2014

SwiftKey keyboard app for Android goes free to download and confirms iOS 8 development - Gadgets and Tech - Life & Style - The Independent

Build platforms that allow people to do things, like Facebook, seem to be the successful business model. Swiftykey gives you the basic software and hopes to sell add ons.

SwiftKey keyboard app for Android goes free to download and confirms iOS 8 development - Gadgets and Tech - Life & Style - The Independent:

'via Blog this'

Monday, June 9, 2014

Buffett Takes Another Shot At The Hedge Fund Industry

Hedge Fund Industry

The Oracle of Omaha recently sent a letter to a San Francisco pension plan, advising the $20 billion fund not to invest in hedge funds. It’s the latest development in Buffett’s tenuous history with the hedge fund world.posted on June 9, 2014, at 11:10 a.m.

Mariah SummersBuzzFeed Staff

AP Photo/Nati Harnik

Warren Buffett doesn’t think it’s a great idea to invest public money in hedge funds. At least that’s what he told a San Francisco pension that sought his advice on the matter last month. The response illustrates Buffett’s long tenuous relationship with the hedge fund world.

A board member at the City & County of San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System wrote Buffett a letter last month, which was obtained by Pensions & Investments, asking his advice on his $20 billion pension fund’s proposed 15% investment in hedge funds as a volatility reduction measure. Buffett wrote back, stating, “I would not go with hedge funds — would prefer index funds.”

Herb Meiberger, the board member, opposed the $3 billion investment plan, and wrote to Buffett after attending the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting last month, where Buffett recounted a story that expressed his lack of faith in hedge funds. Buffett spoke of a $1 million bet he’d made with the hedge fund Protégé Capital in 2008 that a group of hedge funds of Protégé’s choosing couldn’t outperform the S&P 500 index over a 10-year period.

It wasn’t the first time Buffett has criticized or questioned the tactics of the modern day hedge fund world. He has a history of voicing his suspicion on common hedge fund tactics like short selling, as well as the industry’s credentials for capital raising.

But the skepticism goes both ways — hedge fund managers have their doubts about Buffett. At the SALT conference last month in Las Vegas, hedge fund managers took to a panel to discuss Buffett’s returns, including famed investor Leon Cooperman of Omega Advisors and John Burbank of Passport Capital, who called Buffett “basically a tax evader.”

As for the San Francisco pension, the board will vote on the hedge fund allocation, which Meiberger believes is overly risky and too expensive, later this year. It also remains to be seen whether Buffett will prevail in his $1 million bet against the industry that he’s now given even more reason to want to win.

Buffett Takes Another Shot At The Hedge Fund Industry:

Link: http://www.buzzfeed.com/mariahsummers/buffett-takes-another-shot-at-the-hedge-fund-industry

'via Blog this'

Thursday, June 5, 2014

Daniel Yergin on the next energy revolution

Commentary|McKinsey Quarterly

Daniel Yergin on the next energy revolution

The global energy expert and Pulitzer Prize–winning author expects an energy landscape rife with innovations—and surprises.April 2014

The unconventional-oil and -gas revolution—shale gas and what’s become known as “tight oil”—is the most important energy innovation so far in the 21st century. I say so far, because we can be confident that there will be other innovations coming down the road. There’s more emphasis on energy innovation than ever before. Unconventional oil and gas came as a pretty big surprise. It even took the oil and gas industry by surprise. “Peak oil” was such a fervent view five or six years ago, when oil prices were going up.

The unconventional energy revolution Global energy expert Daniel Yergin tells McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland to expect an energy landscape rife with innovations—and surprises.

But I looked at this the way I did in The Quest, which was: Yes, we’ve gone through this period of running out of oil, but we’ve gone through at least five previous episodes of running out of oil. Each time, what’s made the difference? New technology, new knowledge, new territories. And something else that people forget: price. When we look at economic history, we see a very powerful lesson that has to be learned and relearned: price matters a lot. Price encourages consumers to be more efficient. It encourages the development of new technologies and new ways of doing things. Indeed, I think that the impact of price is often underestimated as the stimulator of innovation and creativity.

There are a number of big initiatives and opportunities that could bring changes. Certainly, the electric car will continue to be a big push, as it’s captured the imagination of some people, and a lot of investment has gone into it. Also, public policy is pushing it hard. I think it’s going to take a few more years to get a sense of the uptake, though, because electric cars are competing not with the automobiles of yesterday but with the more fuel-efficient cars of tomorrow. Another big area is electricity storage. If there’s a holy grail out there these days, it’s storage, because innovations in electricity storage would change the economics of wind and solar power.

Distributed electricity generation will increasingly be a big question for developed countries. Electricity won’t just be generated in large, central plants, but through wind power on hillsides and through solar power generated on lots and lots of rooftops. These developments make things much more complicated for the people who have the responsibility for managing the stability of the grid. They also raise important questions about incentives and subsidies that need to be worked out, such as who pays to support the grid? These will be the subject of much debate and turmoil over the next several years as we get our arms around a whole new set of issues.

I don’t know what the pathway’s going to be to solve the problems. But when you have a lot of bright people working on a problem in a sustained way, you will probably get to a solution. Will it be 5 years or 15 years? We don’t know but, ultimately, need drives innovation. I see this as all part of the great revolution that began with the steam engine, and there’s no reason to think it’s going to end. It’s going to continue in the oil and gas industry, and it’s also going to stimulate innovations of other kinds among renewables and alternatives.

We’re not always going to be able to predict where the innovations will happen. Not by any means. But this great revolution in human civilization around energy innovation is going to continue as far as we can see—indeed, much further than we can see. Of course, history tells us that geopolitics can come along and deliver some shocking surprises, but surprises are one of the key characteristics of energy over the long term. One thing we can be sure of: there are always more surprises to come.

Published on Apr 9, 2014

Daniel Yergin, the global energy expert and Pulitzer Prize--winning author, expects an energy landscape rife with innovations—and surprises. The author of "The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World," talks to Rik Kirkland, senior managing editor of McKinsey Publishing, about why he's optimistic about the "unconventional energy revolution," public policy change, electric cars, and distributed electricity generation through solar and wind power.

Watch here and click to find more from our Resource Revolution series on our site: http://bit.ly/McKResourceRevolution.

Watch here and click to find more from our Resource Revolution series on our site: http://bit.ly/McKResourceRevolution.

Category

License

Standard YouTube License

About the authors

Daniel Yergin is the vice-chairman of IHS, the research and data company, and author of

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (Penguin, 2012) and the Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (Simon & Schuster, 1991). This commentary is adapted from an interview with Rik Kirkland, senior managing editor of McKinsey Publishing, who is based in McKinsey’s New York office.

Daniel Yergin on the next energy revolution | McKinsey & Company:

Link: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/energy_resources_materials/Daniel_Yergin_on_the_next_energy_revolution?cid=ResourceRev-eml-alt-mkq-mck-oth-1404

'via Blog this'

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (Penguin, 2012) and the Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (Simon & Schuster, 1991). This commentary is adapted from an interview with Rik Kirkland, senior managing editor of McKinsey Publishing, who is based in McKinsey’s New York office.

Daniel Yergin on the next energy revolution | McKinsey & Company:

Link: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/energy_resources_materials/Daniel_Yergin_on_the_next_energy_revolution?cid=ResourceRev-eml-alt-mkq-mck-oth-1404

'via Blog this'

Wednesday, June 4, 2014

Investment Tweets

Jim Grant: "the most prolific buyers of stock in bull markets are among the most reluctant buyers in bear markets"

information overload got you unable to remember anything? try writing it down by hand

Nasdaq up so much in past year, it has "only" 18.8% more to rise in order to reach its all-time high...set more than 14 years ago #WSJ

An Investor’s Guide to Better Writing — Seriously http://bit.ly/1oTtr52

"The more I learn, the more questions I have." ~Dan Brown

"There must be more to life than having everything." ~Maurice Sendak

Berkshire Too Rich for Buffett ...

Buffett Too Rich for Buffett Is Sign Bargains Are Gone - Bloomberg http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-05-23/buffett-too-rich-for-buffett-is-sign-bargains-are-gone.html …

Twitter / ValueStockGuide: Buffett Too Rich for Buffett ...:

'via Blog this'

Value Stock Guide (ValueStockGuide) on Twitter

Value Stock Guide (ValueStockGuide) on Twitter: "

ValueWalk @valuewalk · May 26

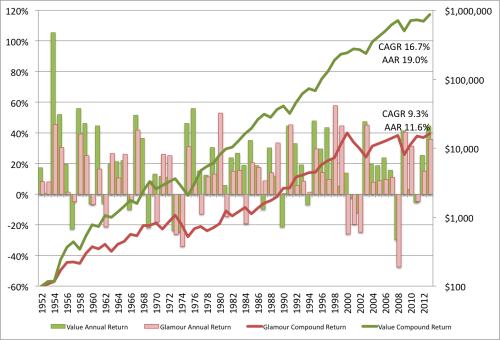

Investing Using the Price-to-Earnings Ratio and Earnings Yield (1951-2013) http://www.valuewalk.com/2014/05/investing-price-to-earnings-ratio-earnings-yield-backtests/ … $SPY $SPX pic.twitter.com/AGcoIzrAF6

"

$SPY $SPX pic.twitter.com/AGcoIzrAF6

'via Blog this'

ValueWalk @valuewalk · May 26

Investing Using the Price-to-Earnings Ratio and Earnings Yield (1951-2013) http://www.valuewalk.com/2014/05/investing-price-to-earnings-ratio-earnings-yield-backtests/ … $SPY $SPX pic.twitter.com/AGcoIzrAF6

"

Investing Using the Price-to-Earnings Ratio and Earnings Yield (1951-2013) http://www.valuewalk.com/2014/05/investing-price-to-earnings-ratio-earnings-yield-backtests/ …

'via Blog this'

Tuesday, June 3, 2014

Lessons Learned From Well-Behaved Investors

Making the Most of Your Money

SEARCH

Lessons Learned From Well-Behaved Investors

By CARL RICHARDS JULY 8, 2013 12:44 PM 21 Comments

Carl Richards is a certified financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

During my time writing for Bucks, I’ve read several comments from different people that share a common theme: “I don’t have any trouble behaving when it comes to investing. So why can’t you?”

If you fall into this group, investing and behaving may appear so simple to you that you can’t help but wonder if the rest of us are short a few brain cells. But your ability to behave is really quite remarkable.

After all, as Daniel Kahneman noted in his brilliant book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” we all suffer to some extent from cognitive biases that make it nearly impossible to behave. These biases often cause us to take mental shortcuts that can thwart our efforts to successfully balance logic and emotion.

In a recent interview with Morgan Housel of The Motley Fool, Dr. Kahneman explains why some people (maybe you?) can better handle these biases. He also discusses why these biases can be so hard to avoid (the portion of the interview presented below was edited out of the video for space):

Morgan Housel: We often hear that Warren Buffett was born hard-wired for the traits that he has as an investor, which sounds nice. But I wonder if there’s any truth to that. Is there evidence that some people are more prone to cognitive biases than others?

Dr. Kahneman: Yes. There certainly are differences among people. There are differences in intelligence and there are differences in cognitive style and the degree to which people check themselves. So some people definitely are more prone to biases than others. That doesn’t mean that they are doomed to be biased. But certainly being prone to self-control and to slow thinking in general, you’ll find differences in children aged 3 or 4, and some of these differences persist into adulthood.

Morgan Housel: So most of these biases are things that we are born with; they’re not traits that we learn.

Dr. Kahneman: The biases that I’ve been concerned with are really characteristics, I think, of the way we’re wired to interpret the world. So in that sense, yes, we’re born with them. I mean we’re born to see patterns, and if seeing patterns leads you into bias, then that bias is built in.

We’re born with our biases. So what’s an investor to do?

Since behavior plays such a huge role in investing — and as Dr. Kahneman notes, these biases are hard to avoid — you need a strategy to keep you on track. The best source for figuring all of this out is watching the people who do behave well. What do they do differently than the average investor?

1) Separate decisions from emotion

I’ve often said that I’m great at making unemotional decisions when it’s another person’s money. But when it comes to my own money, it can be a struggle. Warren Buffett is a perfect example of this principle. Mr. Buffett has said over the years that he tries to be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful. That is essentially putting into practice the notion of “buying low and selling high.” And it means sticking with a plan even when it’s painful (for instance, when stocks suddenly jump or slump).

2) Doing nothing is the default choice

When I heard about the study that found soccer goalies could be more successful by doing nothing, I immediately understood why there would be resistance to the idea that not moving could block more goals. I suspect most of us have a bias toward action, especially if we think we’ll look stupid if we stand still. The best behaved investors understand that it’s in their best interest to do nothing most of the time, even though everyone else around them may be saying otherwise.

3) Understand that investing and entertainment are two different things

I’m the first to admit that reading and watching the so-called financial news can be interesting, even outright entertaining. But those who manage to behave seem to have adopted two approaches: watch it, but don’t act on it or ignore it completely. They’ve drawn a line between investing and entertainment. They may watch and read, but what they see doesn’t sway them from their plan.

Obviously, none of these three things are particularly complicated. So is something more going on? Is it a case of survivorship bias, where the people who appear to behave just haven’t made a mistake yet?

I doubt it. I think well-behaved investors are just better equipped than the average investor over the long haul. But they’ve also done something that the rest of us can do. They have acknowledged the connection between emotion and behavior.

There are no guarantees that we’ll avoid our biases in the future, or that we’ll avoid making mistakes. But simply recognizing that the land mine exists may get us out of some difficult situations or avoid them entirely. So take a look around you.

Do you know anyone who seems particularly well-behaved? How about someone who bought something like a low-cost index fund and then stayed put for 10, 15, even 20 years?

What have you noticed about them?

Maybe I’ve misjudged the situation, and perhaps it isn’t possible to behave over the long haul. Still, I’d like to think that we have enough examples from well-behaved investors to learn from. And that can help make the seemingly impossible become more probable for the rest of us.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)